rocket emoji securonomics?

2 months into a new government, there’s been a vibe shift on tech. True believers need to win the argument

We’re 2 months into a new government. For tech, there’s been a vibe shift.1

Why are some folk a bit jittery?

Not only are the weirdos and misfits that built ARIA, AISI and 10DS now out, but they haven’t been replaced at all.

Tech has been moved out of the centre, with no residual capability in No10.

Compute infrastructure is in limbo. Labour has plenty to say about tech in government & public services, but less to say about AI, startups, strategic advantage, and the broader innovation economy.

The Home Office quickly slapped down any talk of lower visa costs, and wasn’t reined in.

What does the bull case look like?

The new government’s focus on service and stability is a huge contrast to the last’s.

We’re only a few weeks in. Mission Boards have just been set up, and announcements are due on the AI Action Plan and Regulatory Innovation Office soon. The new government deserves time to set out its thinking.

GDS & CDDO’s influence had waned in the Cabinet Office anyway. Their move with i.AI is not so much a weakening of the centre, but a promotion for DSIT: its role today is now akin to a tech-native Cabinet Office, with a cross-government mandate to match.

Labour has made some unequivocally top tier appointments — Sir Patrick Vallance, Matt Clifford, Varun Chandra, Emily Middleton — so they are accessing the necessary expertise. True, these aren’t like-for-like replacements, but the capability has been recreated & augmented in the aggregate.

The temptation to centralise power was really a response to a failure mode of bygone department-led delivery. There is a path to progress where these appointees, and DSIT more broadly, are empowered to lead.

What stops us fully believing this theory is that it requires dedicated political and intellectual sponsorship for science and tech from No 10, possibly with specialists in DSIT, to back up appointees, advisers and officials when necessary.2 It’s clear that Lord Vallance’s de facto advisory role makes him more than just a Junior DSIT Minister. But there’s little dedicated empowerment direct from the centre. For the sake of 2-3 headcount, why not?

Without it, promising appointments will at best end up fighting against the grain – for attention, funding, and impact – and at worst be cut adrift from a centre that looks like it fundamentally lacks interest or instinct.

This is particularly important in the AI era, which requires every department to take responsibility. There’s a risk that Labour gets stuck catching up to the last decade of technology, focusing only on DSIT. But tech is not just a sector or stakeholder: it’s both a necessary force and an urgent opportunity, requiring every Minister to rewire their departments to accelerate wider economic & societal progress.

In absence of this steer, momentum could wane. Other Ministers will (and may already) be captured by the swirl of structural incentives, media crises and other well-intentioned but ultimately distracting initiatives that combine to form ‘the Whitehall machine’. AI quickly becomes a ‘nice to have’, or is discredited as simply ‘hype’, to avoid making changes too quickly. Already, turf wars have broken out over manifesto commitments. With a difficult Spending Review on the horizon, friction will build further. In the past, No10 and HMT clearly signalled that DSIT would win these battles by default. That backing isn’t yet obvious today.

Leadership matters.

If you believe that exponential scientific and technology progress will define our future, then you need to be much more strategic about building a stake in that future as early as possible. It will affect the economy, jobs and our politics, whether we’re prepared for it or not. NVIDIA alone shows how technology shifts quickly lead to economic and geopolitical reordering: similarly, unfocused countries can quickly sink, while others rise.

Inertia isn’t an option.

AI holds the potential to create a powerful cycle of growth. It could also be a force that replaces jobs, fosters inequality and leads to a potent populist backlash. Even AI-sceptics implicitly admit that its long-term impact depends on how we develop and deploy it. If our ambitions are modest – to use AI simply to improve efficiencies and reduce costs – the benefits will be modest, too.

Yet if we use AI to rethink everything from health care and education to food production and energy generation, then the potential of AI is to reallocate and relocate human economic activity in a way that wasn’t physically possible even five years ago. The economic and societal gains would be significant.

Golden ages are not accidents. They can be missed, slowed down or accelerated by political choices. There are many possible futures, and we can shape and choose the ones we prefer. Do we want to grow our stake and say in the future, or be price and technology takers forever?

Time for new idea machines

Labour needs holding to account, to offer its own vision and political story for technological progress. It needs to make the leap from saying nice things about the importance of the tech sector, to really weaving it into a progressive narrative and spending political capital like it has for planning, infrastructure, energy and public service reform.

For those other areas, the government's job is a director, funder and project manager to unlock tangible value today. But those who are most excited about technology aren’t just motivated by efficiency gains or ‘digital transformation’, but by the power of emergent, experimental, curiosity-driven serendipity. This requires less marshalling and controlling, and more faith.

Take startups: they’re not just the most productive part of the economy and employers of the future, they’re the delivery unit of progress. They’re critical to Labour’s missions! They are hypotheses, speculations and blueprints for possible futures, just expressed in the form of a company. Today, they represent hazy, low-fi fragments of the future. But with optimism, agency and ambitious structural reforms, we can bring them into focus.

So far, Labour hasn’t quite developed its own instincts here. But that just means true believers need to win the argument. Those evangelising about tech and then complaining that Labour doesn’t ‘get it’ need to change tack. Nor can the vacuum be filled only with calls for regulation & stakeholderism, at the expense of material progress & prosperity. This is sales 101: first you need to understand demand, rather than simply pushing supply. Making things people want > making people want things.

So what does that demand look like?

Labour won the general election by promising change. And given the government’s adopted the core message that ‘Everything’s not awesome’, Labour will want to deliver change - to deliver progress - as quickly as possible.

The last government was occasionally vibes-y and credulous, but it had a rigorous diagnosis about securing strategic advantage through science and technology. Instead, Labour’s default looks to be technocratic managerialism and stakeholder engagement. But that way lies reactive, low-conviction governance, not the proactive, strategic statecraft needed to capture this moment. This will not change the long run trajectory of the country. It will not deliver outlier economic growth.

How do we make the case for a different approach? We need to build a new world that not only champions science and tech progress, but one that connects to Labour’s priorities and values. Otherwise, you’re just shouting into the wind.

In effect, we need a new “idea machine":

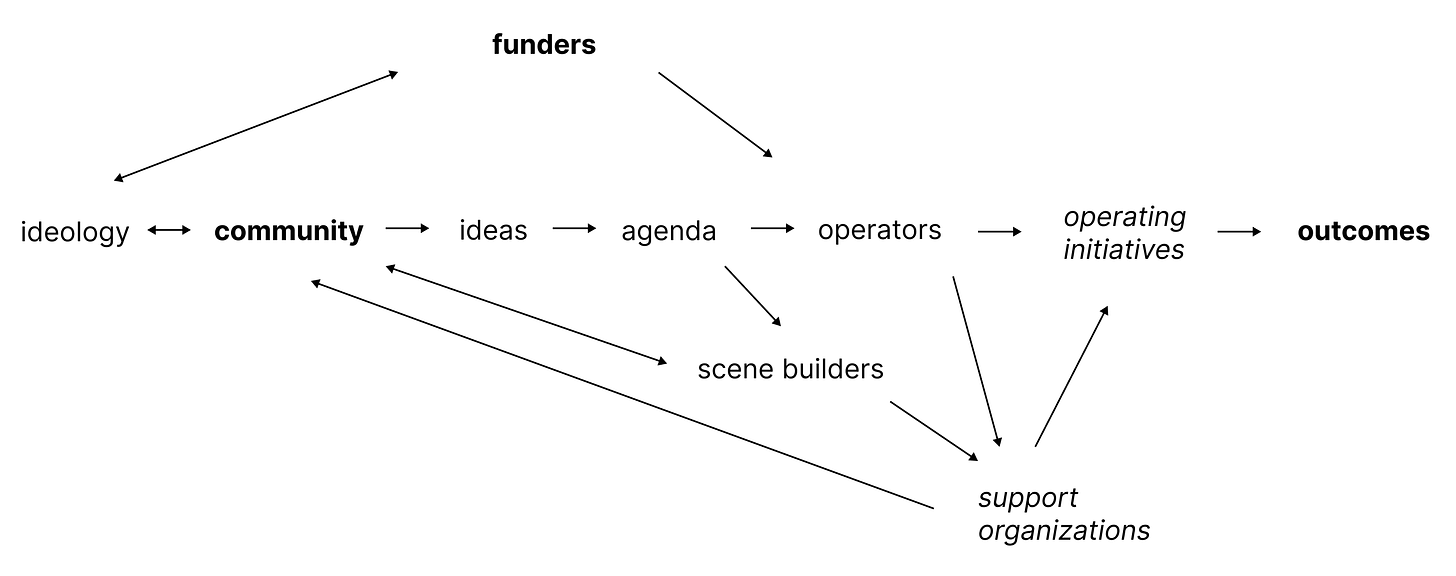

a network of operators, thinkers, and funders, centered around an ideology, that’s designed to turn ideas into outcomes

As Asparouhova sets out, an idea machine:

is a self-sustaining organism that contains all the parts needed to turn ideas into outcomes:

It starts with a distinct ideology, which becomes a memetic engine that drives the formation of a community

The community’s members start generating ideas amongst themselves

Eventually, they form an agenda, which articulates how the ideology will be brought into the world. (Communities need agendas to become idea machines; otherwise, they’re just a group of likeminded people, without a directed purpose.)

The agenda is capitalized by one or several major funders, whose presence ensures that the community’s ideas can move from theory to practice – both in terms of financing, as well as lending operational skills to the effort. (Without funding, an idea machine is just that: an inert system that needs fuel to turn the crank and get it moving.)

This approach is about building a durable coalition that’s bonded by vision and values, not just transactional, ephemeral asks from trade bodies.

To really get buy-in, it should attract, but also repel.

A UK idea machine for technology-driven progress in the UK is likely focused much more on security, sovereignty and public value. It’s not scared by the words ‘industrial strategy’, but can focus these efforts on creative disruption instead of incumbent subsidy.

It connects signals from the frontier to the policy problems of today, putting people and problems first, technology second. It takes the opportunity of science and technology as central to future-proofing our economy and society, and to building resilience in an increasingly competitive and volatile global environment.

This machine should also inspire insiders to want to spend time in this world. Too many startup, science and tech policy discussions can be super boring, focused only on economic or transactional issues. While important, they’re rarely captivating. But we can choose to see the magic.

It’s time to fire up a new idea machine. Who’s for rocket emoji securonomics?

Personal views, not those employers

It was a shame to lose great specialists appointed by the previous government. But it can hardly be a surprise that a new government might not trust them.